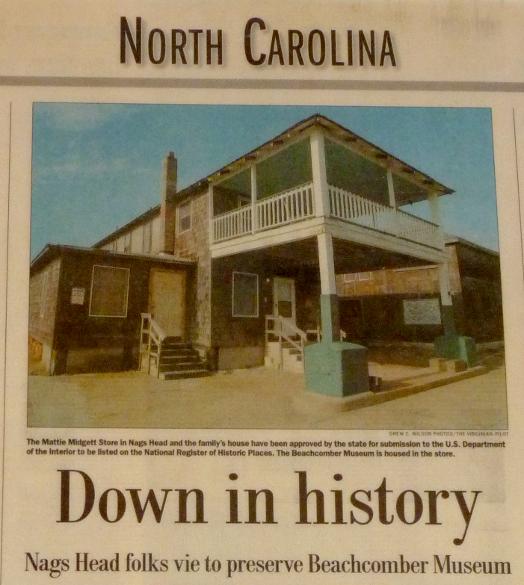

Article in the Virginian-Pilot, November 25, 2004:

By CATHERINE KOZAK

NAGS HEAD — Way before tourism became an Outer Banks industry, Mattie Midgett’s store served

a summer population at what is now Soundside Road and the Cottage Row Historic District. Over the

years, Midgett’s daughter, Nellie Myrtle Pridgen, had appointed herself the tough-as-nails guardian

of the cottages.

But Pridgen’s most notable legacy is her astonishing bounty of beachcombing booty: glass, porcelain,

pottery, arrowheads, bottles, jars, tiny dolls, rare shells and stoneware, fulgurite, ancient rocks

and plastic toys.

The Mattie Midgette Store – the name is also spelled Midgett – and the family’s house were approved

this month by the state for submission to the U.S. Department of the Interior to be listed on the

National Register of Historic Places. Next, the goal is to have The Beachcomber Museum, housed

at the store, open year round.

"It fits right in with the Lost Colony, the First Colony and the Wright Memorial," said Carmen Gray, 67,

Pridgen’s daughter, as she stood in the museum, surrounded by her mother’s treasures. "I feel like

we are just as an important part of the history to the county. We don’t have any people that come

in that don’t seem to be interested. They all want to stay for hours."

Nags Head has a case of Pridgen’s relics displayed at Town Hall, but Gray said that few, if any,

town officials have come to the museum or seem to appreciate its value to the town.

"It’s strange," Gray said. "They’re not that interested."

After a visit in May, Bruce Bortz, the deputy planning director in Nags Head, told museum organizer

Chaz Winkler that a number of things would need to be done before a museum would meet with

town building codes, and he suggested that a proposal be submitted to the planning board.

Bortz said last week that the building, zoned commercial, does not meet setback requirements and

would have to make some adjustments to accommodate parking, including the possibility of more

paving. The historic designation, he added, could perhaps relax some of the building code regulations.

Nags Head is willing to work with Winkler and the museum, he said, but the town needs information.

He said that nothing has been presented to the planning board.

"I think the difficulty he sees is he comes in with a vision, and that vision does not meet our zoning,"

Bortz said. "It has to go beyond that. ... The town hasn’t said no to anything. They have shown us

some surveys that wouldn’t work. He would need to present to the town an array of

town zoning amendments."

The grocery store, built in 1914, was rolled on timbers from the sound side to the ocean side after

the 1933 hurricane. When the store was in place, the family’s house was built behind it. In the 1970s, after the death of her parents, Pridgen moved into the old store, where she began carefully

organizing the best of her collection.

Although it has been reorganized somewhat, much of it is as she left it. The museum also displays

ledgers documenting the 58 years the store was in business.

Winkler and his partner, Dorothy Hope , live upstairs from the museum, which fills the space where

the old store once displayed its goods for sale. He said that the idea is to run the museum like a

business, with people living there and making a living from running it.

"That’s the tradition of it," he said. "We’re going to restore that back house and refurbish the site

in the original condition. ... At some point, our vision is that people could come here and see what

old Nags Head used to be like."

The town has allowed the museum to be opened on an informal basis, with the restriction that it not

advertise or charge admittance. Last year, the museum opened for 40 days around the time of the

First Flight Centennial, and for two nights especially for the town officials. But none came, Gray said.

When the museum reopened on a recent Saturday, Gray said, she guesses at least 150 people came.

One recent museum visitor was impressed by the enormity of Pridgen’s collection.

"There’s a little bit of everything there, from human to natural," said Stan Riggs, distinguished

research professor, department of Geology at East Carolina University.

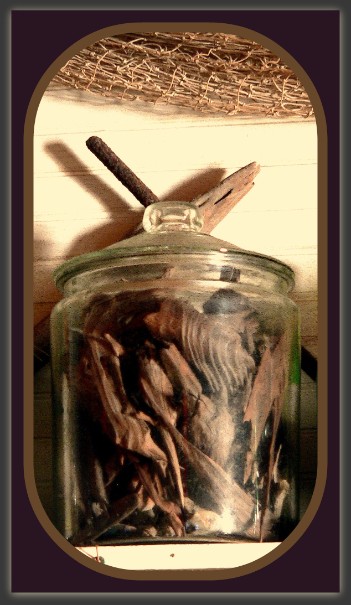

An old glass candy jar is now filled with polished red cedar heartwood.

GERMAN STONEWARE:

"A ware of the Renaissance period, fired at a temperature so high as to vitrify the body and render it impervious to liquids, without a coating of glaze. The body was relatively coarse, the forms roughly "thrown" and the surface covered with molded pictorial ornament. Some of the earliest of this stoneware is ascribed to Cologne, where the so-called Bellarmine (q.v.) or greybeard jugs are thought to have originated. Many pieces of this stoneware found their way into England early in the 16th century."

He could tell that some of the items came directly from the

tropics, pushed in from the Gulf Stream. Others were thrust

onto the beach during storms, often stirred up from the sea

floor. Barnacles on bottles and other artifacts also tell stories about their origins.

Riggs said that much of what Pridgen scooped up off the beach and dunes may have been from hundreds of years ago.

The fulgurite – lightning glass – displayed at the museum,

or the pieces of polished heart wood of pine likely will never

be found again, Riggs said. Same with much of the more

interesting artifacts that she found, like the top of a German

stoneware bottle that perfectly matched one from a 1629

shipwreck that Pridgen saw in an edition of National

Geographic.

"They’ve been mined," he said. "The possibility of finding the

kinds of things that she found is virtually impossible – even

after a storm." But Riggs said that the collection’s value is

more historical and educational than scientific.

"If I knew exactly where all that stuff came from, then it would be different," he said. "The fact that it was just on the beach is more of a curiosity."

(continued below)

________________________________________________________

____________________

Below: A 16th century "Bellermine" jug top Nell found on the beach in 1982.

continued...

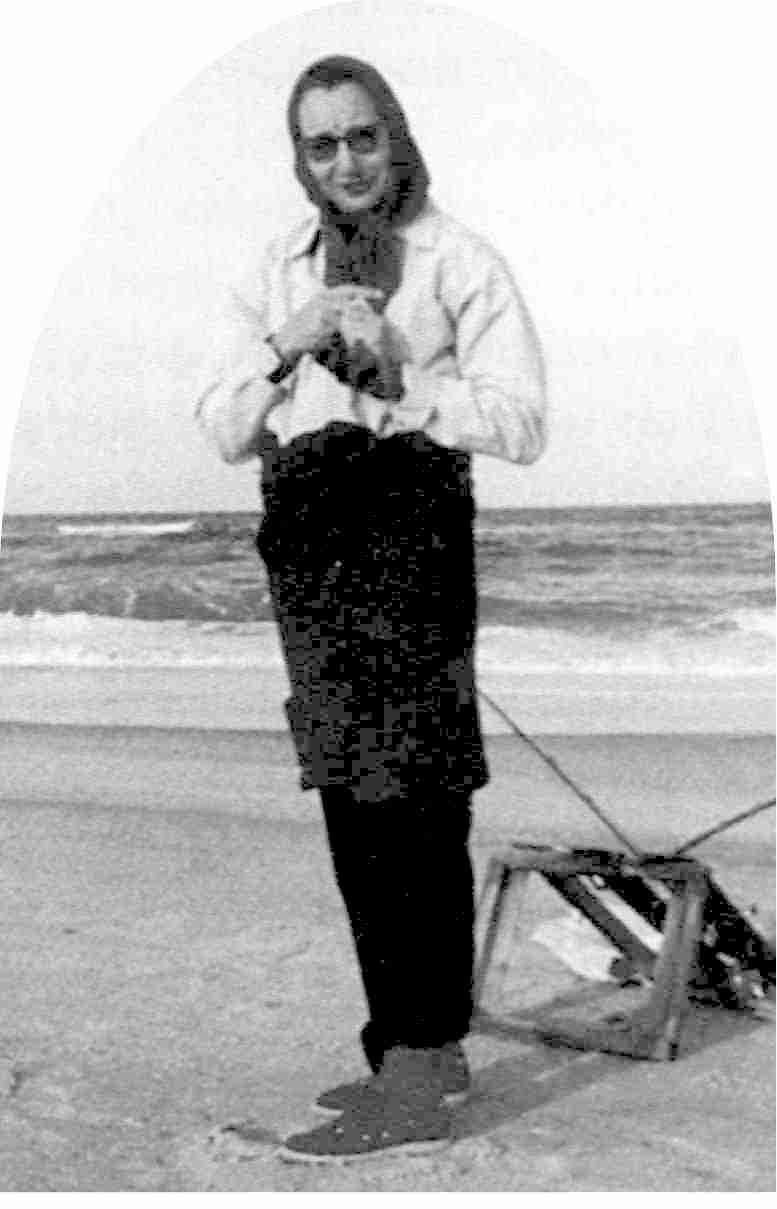

For most of her 74 years, Nellie Myrtle – as everyone called her – walked at dusk and dawn, day in and day out, along the oceanfront, the sound side and the dunes at Jockey’s Ridge, scouting for beach glass, bottles, old dolls, anything interesting that the sea tossed aside or the sands gave up. By the time she died in 1992, she had amassed jar after jar of sea glass, sorted by color; seashells of every distinction; colorful plastic toys that fill a big basket; bottles of every color and size, some containing messages; and numerous artifacts dating back hundreds of years.

To Joanne Schreiber, founder of Between the Tides for SEA Glass Enthusiasts, just seeing a sample of Pridgen’s collection was impressive. Schreiber is also the producer of the First Northeast Seaglass Festival, held October 9, 2004 Rockport, Mass.

Carmen and Billy Gray, along with museum volunteers Dorothy and Chaz, took some items to display at the festival, which was attended by 575 people from 14 states. "What I did manage to see of their exhibit was phenomenal," Schreiber said. "Definitely, Nellie Myrtle’s collection was so enriching."

Schreiber said that as far as she is aware, there is no other beachcomber’s museum in the country.

And there might be no other place that encapsulates the evolution of Nags Head better than the Midgett store or Nellie Myrtle Pridgen.

"Let’s put it this way," said Outer Banks historian David Stick, "I would say next to Jockey’s Ridge and the Wright Brothers Memorial, it is the most historically significant place on the northern Outer Banks. It is an integral part of the Nags Head Historic District."

Stick, 84, who went to elementary school with Pridgen, said she had few friends "because she irritated everyone." But he enjoyed her intelligence and vision about the environment. He also reveled in her propensity to express strong opinions, which she freely told him in her very distinctive voice.

"She was right about so many things, " he said. "We kidded each other back and forth and she was quite a character."

Nellie Myrtle, circa 1942

Carmen Gray said she believes that, although her

mother disliked tourists, she would want folks to

appreciate her beachcombing treasures and see

what her beloved community once offered.

"What a wonderful calling card for Nags Head

and for Dare County," she said.

END ____________________________________________________

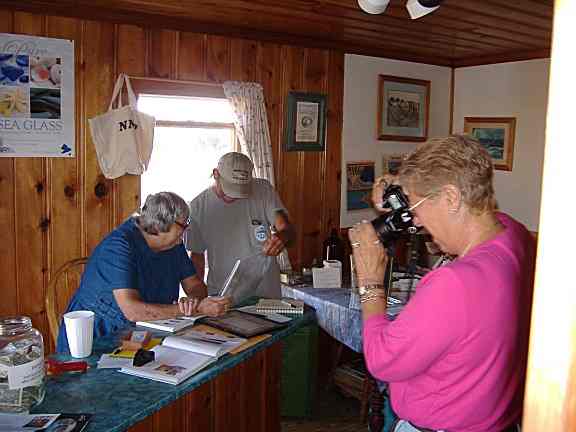

Photo: Carmen Gray searches for answers to

an Open House visitor's question as museum

volunteer Martha Price photographs a rare,

newly discovered Dutch Gin bottle bottom in the

Fall of 2006.

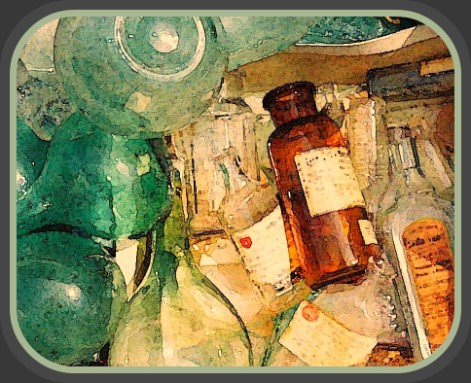

Here the Gin bottle bottom Nell found is seen with a page from "Pure Sea Glass", a book by Richard LaMotte featuring a collection of old bottles that are likely to be the origin of some of the beach glass pieces picked up by seekers of these vanishing gems.

Photo by Martha Price

Copyright © osob.net 2019

__________________________________________________________________